Here we begin our How To Think Like a Futurist series!

The first way to think like a futurist is to notice the ways you already do.

There are three basic ways to be a futurist:

First, to contingency-plan and strategize for the arrival of whichever possible future emerges. This is the bread-and-butter work of most professional futurists. They discern what future landscapes are possible and plan to take advantage or cope with the opportunities or dangers that lie ahead. This is how and why my Possible Futures for American Democracy newsletter is structured the way it is.

Second, to plan to outlast as many futures as possible – to play defense. In Simon Ramo’s classic book Extraordinary Tennis for the Ordinary Tennis Player, Ramo studied a large number of tennis matches and realized there are two versions of tennis — one played between professionals and one that’s played between amateurs — and winning and losing happens completely differently in each kind.

His study showed that when professionals competed against each other, 80% of the points each competitor won was due to an action they took but when amateurs competed 80% of their points were won by receiving points every time their opponent made a mistake. Professionals won their matches; amateurs who won simply failed fewer times and thus were handed their victories. Professional tennis players, Ramo argued, should play to win; amateurs should try to win by not losing.

Your savings and retirement accounts, your insurance policies, and some of your strategic purchases are you already acting and thinking like a futurist by trying to win the future by not losing. (Organizations like The Long Now Foundation and the Svalbard Global Seed Bank are outlast-disaster endeavors. Much more on them in future newsletters.)

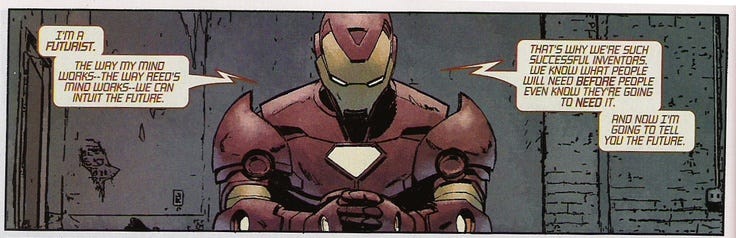

Third, to create the breakthrough innovations or insights the world needs and/or to advocate for change. In short, to create, launch, or enable a future. When you create, you’re thinking and acting like a futurist. (Also: you may be a pioneer, a test pilot for the future, or both like Tony Stark a.k.a. Iron Man.)

More on all of these in the newsletters to come.

What’s important right now is this: to operate as a futurist in any of these ways you must start first with a realistic understanding of the landscapes ahead so your strategies, outlast-defenses, and creation efforts match those futures. If you generate a mismatch (or get the cart before the horse) what you yield won’t be relevant, needed, and helpful; you may poison or destroy what you love.

(This is one of the roots of why the Southern Baptist Convention turned so fundamentalist and toxic. And it’s one of the reasons why America is secularizing. Sort of. But not really. More on these in the next few weeks when I review The Great Dechurching, talk about evangelicals “deconstructing” their theological belief systems, and more.)

But here’s a bonus twist: you also need to know the narrative of the future held by your client group because if there’s a mismatch there, then there will be many problems ahead.

When I work with a church I try to discern what that congregation’s theology of the future is — its narrative about/orientation toward the future — as soon as I possibly can.

See, there’s three different conflicting views on the future in the Bible. (These were discerned by Harvey Cox back in the 1970s. He published them in an article I cannot locate right now. My Google-fu has failed me.)

There’s the Hebrew prophetic view that presents the future as open and undetermined. While God has benevolent intention for us and for our futures God hasn’t predetermined their outcomes. And since God created us in God’s image — the Creator made creators — our job is to co-create the future with God. (This is the view in most of the Old Testament and by Jesus most of the time throughout the Gospels.)

There’s the Greek teleological view that asserts that God has the future all preplanned and our job is to adhere to the plan… but not to make plans of our own. (This is sometimes the view presented by the Apostle Paul in the New Testament and only once or twice by Jesus in the Gospels.)

And there’s the Persian apocalyptic view that asserts that the end of the world is coming soon, it’s a blazing end, and our job is either to pack our bags to shuffle off this mortal coil or to hunker down to outlast it. (This is the view in Daniel and others written in that same time and place, in Revelation, and once or twice by Jesus in the Gospels.)

If the church you’re working with holds the Greek teleological or Persian apocalyptic views then the clergy and congregation won’t want to try to discern the future — they won’t think they have to. They think they already know what the future will be. And they’ll ignore or resist your efforts to help them discern and plan in realistic ways.

What’s the corporate version of this? If the company believes their industry is stable and will or can only progress along its present course. In that case any future that looks like a deviation from that assumed future means you are calling into question the client group’s own infallibility and wisdom and you may become a threat or a nuisance. If you are a futurist who’s already within their workforce and you do this then you may be viewed as a malcontent, disloyal, or simply dumb.

And if YOU hold the Greek teleological or Persian apocalyptic views then you may not reeeeeeally be a futurist; you may just be a doomsday prepper.

Know thyself. Then get a cup of coffee and we’ll get to the tough stuff soon.

Thanks, Cass, for this post on describing various ways to be (or not to be) a positive futurist.

I have always liked the Merlin the Magician Approach (was that a Joel Barker thing?) of visualizing the future like you were living in it, and then strategizing (with flexibility and agility built in and every 120 days evaluations) how to get from where we are to that desired future.

With churches I get them to craft a Future Story of Missional Ministry that visualizes seven years from now on strategic things, and – for those church leaders with any future skills – 50 years into the future regarding their institutional characteristics – like buildings.

This is based on the pattern of Leviticus 25:1-12 looking at a every seven-year sabbatical and then every 50 years of jubilee.

What type of futurist does that make me?

George Bullard, Centrist Baptist Maverick

Good stuff, Cass!