In Case You Know Someone Who Is Dying, Has Died, or May Die in the Future

About light bulbs, electricity, and heaven.

Cassidy Steele Dale writes to equip you with the forecasts, foresight skills and perspectives, and tools you may need to create a better, kinder world.

And one of those ways is to talk about the ultimate future ahead for each and every one of us.

Years ago a friend of mine was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He knew he wouldn’t survive; he could only buy time.

He asked me what Christians believed about death, dying, and the afterlife. He said only his rabbi and I would even discuss it with him. He said he knew I wouldn’t give him platitudes or ministerial parlor tricks about it; I’d give him some real answers.

I told him I’d write a letter. One that he could show his family and leave for them later.

Here’s what I wrote:

Dear ____,

I have had a few thoughts.

In most of the world religions, there tend to be two types of ways of talking about death and what comes after. The two types are usually rooted in the two major religious orientations—the exoteric way and the esoteric way. (I go into the differences in more depth in The Knight and The Gardener in the “Soul” section.) Every religion is both exoteric and esoteric, but different traditions emphasize one over the other.

In short, exoteric religions are dogma-and-“fact”-based and treat religion as if it is akin to science or engineering or law. The workings of God are known, fully mapped out, and theology is like a reliable, valid architectural schematic.

Esoteric religions are mysticism-based and treat religion as if it is like art or poetry—that it conveys truths about The Beyond that are barely/inadequately express-able in human language. The nature and character of God are known but the Spirit moves in mysterious ways.

For example, the great Christian mystic Thomas Merton spent the last decade of his life exploring the mystic revelations and wisdom that Catholic and Zen Buddhist traditions had arrived at separately and independently. Merton died at a conference (he was accidentally electrocuted) of Catholic priests and monks and Buddhist priests and monks. The priests of both religions (exoterics) argued about “the truth” (whose dogma was right) morning, noon, and night while the monks of both faiths (esoterics) prayed and meditated together and played ping pong and didn’t argue a bit. The monks all knew they were saying different things but were nonetheless tuned into the same spiritual channel.

Exoteric religious people tend to treat depictions of heaven as if they are reports of factual realities about the afterlife… that heaven is puffy clouds, is in the sky, that God wears robes, that there are pearly gates, etc. Exoteric atheists, though, tend to scoff at those depictions as being factually absurd. Since exoteric religious people and exoteric atheists both treat religion as if it is like science, they fight over dogma and belief as if they are competing literal-truth claims. That’s how we got the science-versus-faith debate — and those debaters.

Esoteric religious people and esoteric scientists (of which there are many) realize that their explanations are parallel claims—that one is talking about the mystical world of the heart and soul and nature of God and that the other is talking about realities of the physical world. They’re complementary, not competing.

Esoteric religious mystics depict death and the afterlife very differently than exoteric dogmatists do. I’ll come back to that in a minute.

“The Grand Egress”

I told you “The Grand Egress” story last week. I was able to find comparative religions expert Joseph Campbell’s tale about “The Grand Egress” but couldn’t find an account of his final weeks and months. I think it’s in the book Fire in the Mind, a biography of Campbell, but I can’t find my copy of it.

Campbell didn’t talk about death or the afterlife very often because he ultimately focused on what mythic stories do for us in this life. He also was fairly glib about it most of the time.

Most often he told a story about the early days of the Barnum & Bailey Circus, back when it was still a traveling tent show. Patrons would enter particular tents to see oddities and marvels – The King of the Gorillas, that sort of thing – but would get so transfixed that they wouldn’t leave. And thus Barnum couldn’t create enough capacity in the tent — enough flow-through — to get more ticket-paying customers in. Thus he couldn’t sell more tickets. Finally, Barnum posted a sign above the tent exit that read “The Grand Egress” and patrons would exit thinking there was another feature ahead… and discover themselves suddenly outside. Campbell would say that stories of heaven were simply tricks… simply “The Great Egress.”

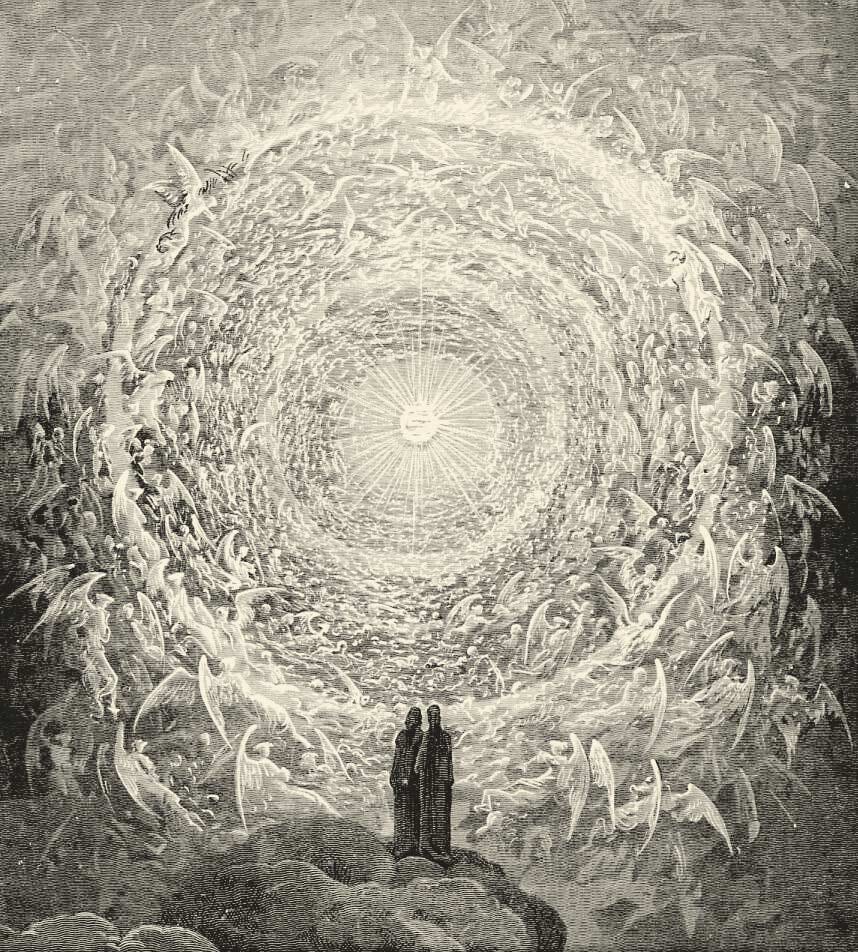

Campbell changed his tune, though, during his own last days. His bout with cancer was short – weeks to months, I think. He spent his final time in a Catholic hospital in a bed underneath a crucifix on the wall. He told his wife and one or two of his best friends that he had spent a lot of time staring at the crucifix and thinking about it. He said he had begun having something like mystical experiences, or at least that the meanings of the mystics’ expressions about heaven had finally begun to dawn on him. He realized that stories of heaven weren’t escape-chute stories; they were mystics’ explanations that when we die we commune with the divine.

The mystic explanation

The major Christian mystics (and Jewish and Muslim and Buddhist mystics) tend to repeat the same few revelations.

First, the mystics are aware that something beyond us exists. But it’s not just out there, it’s also here and now even though it’s not visible to us. Fish don’t see the water and we usually don’t see the air and yet it is what we move through all the time. The divine is present, real, and all around us. Glenn Hinson’s prayer “Let God’s love-energies fall on me” doesn’t invoke as much as accept that God’s love is always on us already.

Second, we are part and parcel of The Beyond. We move through it and it moves through us in the here and now. We’re not separate from it like stones are separate from water in a stream; we’re all part of the water and we’re all made of water.

There’s a theological typology that helps on this. There is theism – the notion that God exists. There’s atheism – the notion that there is no God or divine. There’s pantheism – the notion that one is divine. (Usually a heresy.) And there’s panentheism—the notion that we are within God and God is within us. That we are created by The Creator to be mini-creators with him/her. The mystics tend to be panentheists.

Third, we don’t end when we die.

Many people think that the afterlife is what happens after I die. For esoteric mystics of all the major faiths, there’s more: you tap into The Life Eternal now and you’re reunited with it after you die. The Life Eternal is like a river flowing underground you tap into the way you tap into groundwater. The Life Eternal existed before each of us were born, is underneath us now, and we rejoin it later. It’s beyond time. The eternal life includes but is more than merely a life everlasting into the future. That life everlasting is also available starting right now.

Mystics differ on what exactly happens when our bodies die, but they keep repeating that our souls or our most essential natures or cores return to commune with the divine rather than are blown away like dust or leaves. The Beyond cares about us individually and we return to the bosom of the divine when our physical lives end.

Fourth, we are reunited with our loved ones when we die. We all return to the main, and we all remain connected to the ones we loved when we were alive.

What all this means is that when the mystics talk about the divine, about who we are in this life, and what happens after we die, they tend to say things like…

We are fingers or tendrils of clay that were rolled out from the main lump. Though we as tendrils are thin and wispy, we remain manifestations of/part and parcel of the main. When we pass away we are simply folded back into the main.

We are raindrops that fall silently back into the sea.

We are surrounded by the divine as if it is the ocean and we are in a rowboat. We occasionally dip a hand over the side and feel the water and know that it is there and know what it is and know some of what its nature is. The water is fearsome because we cannot see far down into it, and because we fear we will drown. When we die, we gently lose our balance and tip backwards out of the boat and into the water and find that we were amphibious all along.

In terms of our work, the world will be fine. As Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice. And it has been. We are winning. Slowly, but we are. You have contributed to the world’s well-being. You still are. You still will. Even after you’re gone. Your impression is upon we who have known you. And your impression is upon your children.

Your family will remember you, and they’ll remember the lessons you tried to teach them, and they’ll remember the love you’ve had for them, and they’ll know that your love for them will be present at every single future moment of their lives. You’ll still be with them. They’ll still hear your voice in their heads when they need you. And because the eternal life is outside of time, you’ll be reunited with your family later in the blink of an eye. You will not be apart from them for any of your awareness.

As for what to tell your family, you can tell them anything of what I’ve said here.

But if none of that helps, then tell them something Joseph Campbell once said:

Tell them your body is just a light bulb and just because a light bulb goes out doesn’t mean there is no electricity.

I have been, am, and will forever be grateful to be your friend.

Cassidy

See you next week, everybody.

Having recently losing mom this piece was moving and comforting

This is wonderful reading!